Wayning Interests

Category: 1990s

September 19, 2013

LONDON MAULING

In case you hadn’t heard, Grand Theft Auto V was released this week with a record-breaking $800m in day-one sales. Wow. Things have come a long way from the original GTA, 1997’s top-down world simulator quite unlike anything else on the market at the time. You played the role of a thug coming up in the criminal underworld of any one of three metropolis: Liberty City, San Andreas and Vice City, each tougher than the last. The approach: steal and kill for glory and respect.

For twelve-year-old me, it was like video games had grown up (despite the juvenile take on the subject matter). Here was a game that used the word ‘shit’! When you died, it didn’t say ‘game over’; instead, huge yellow letters gleefully informed you that you’d been ‘WASTED!’, as if you couldn’t tell. If you were nabbed by the 5-0, you were ‘BUSTED!’ – this never happened to Super Mario.

However revelatory the original game was, however technically impressive and more complete the later 3D games felt, my favourite of the series remains largely forgotten. In 1999, on the eve of the release of the highly anticipated GTA2, Rockstar released an add-on for the original. Presumptuously titled ‘Mission Pack #1’ (there would be no #2), GTA London 1969 put a fascinating spin on the original concept. Where the first GTA had attempted, through its tone, its sense of humour and its (awesome) soundtrack, to immerse the player in the now, GTA London casts you back to – you guessed it – 1969, and attempts a similar level of immersion. By choosing a real-world location and a specific era, Rockstar set themselves a pretty lofty goal.

You’re given your choice of four likely lads to unleash upon the unsuspecting London: stoner Charles Jones, proto-punk Sid Vacant, well ‘ard geezer Maurice Caine and mod Rodney Morash. It’s purely an aesthetic choice. Regardless of who you choose, your in-game sprite is the same yellow jumper-wearing goon from the first game. If you’ve played GTA to death and are excitedly jumping into new missions in London, it’s an eerie sight to see what could be Kivlov or Travis waging war across the pond.

And that’s not the only jarring aspect. If you’ve adjusted to driving on the right hand side of the road in the US-based original, get ready for a cruel surprise in London. Rockstar have smothered the game in all kinds of UK-style slang, too. Where the first game was full of bent cops, rastas and mobsters all adhering to the broadest of stereotypes, you won’t get far in GTA London without knowing a ‘prat’ from a ‘ponce’, or ‘the monkey’ from ‘the cheese grater’.

Your thug is working for the Crisp Twins, businessmen brothers whose legitimacy is about as kosher as a sausage synagogue. You tear around a scale approximation of London featuring all the good parts and plenty of the bad. The entire palette of the game feels drab, and as such it’s not hard to imagine the gloomy grey sky above the city. When you’re busted in this one, ‘YOU’RE NICKED’, and when you’re wasted, ‘YOU’RE BROWN BREAD’. Cultural references abound: you’ll upstage a James Bondian secret agent, help Lord Lucan disappear, jack a big red double decker bus and drive one of those stupid Union Jack Austin Powers cars while listening to a pirate radio station. Feel like you’re there yet?

That’s all before the best part of the game. The GTA games might be as well known these days for their extensive licensed soundtracks as for their brutal violence, but it wasn’t always that way. The first game has an entirely original soundtrack spanning all kinds of genres (and as I’ve said, it’s excellent), but GTA London was the first time a GTA game featured licensed music. And what a soundtrack it is: Trojan Records superstars like Harry J. Allstars, the Upsetters and Symarip to Italian cinema maestro Riz Ortolani find themselves remixed into 1969-esque radio stations that are absolutely unforgettable once heard. It’s the same keen ear at work behind the scenes picking the perfect songs to set the tone as in the modern era of GTA games, and it’s just as much of a success for it. You can even put the PlayStation disc in your CD player (remember those?) and listen to the soundtrack that way. As you’d expect, it makes for great driving music.

As the series grew in notoriety it’s easy to understand why Rockstar have never gone back to London. Setting the level of violence the fans expect in a virtual ‘real’ city would cause outrage beyond imagination, even if the level of detail put into Vice City or San Andreas makes it no less ‘real’. But that’s okay, GTA London is still there whenever you want to blow it up, not that that was ever the point. The game’s greatest impact and legacy remains its soundtrack. So…let’s blow it up again.

June 1, 2013

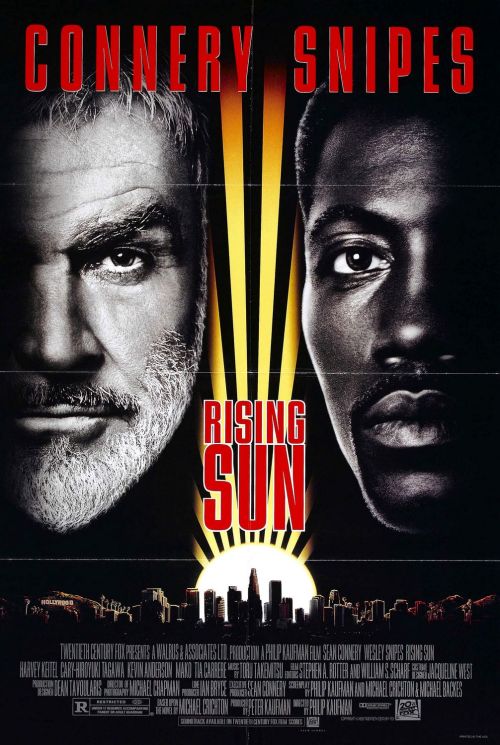

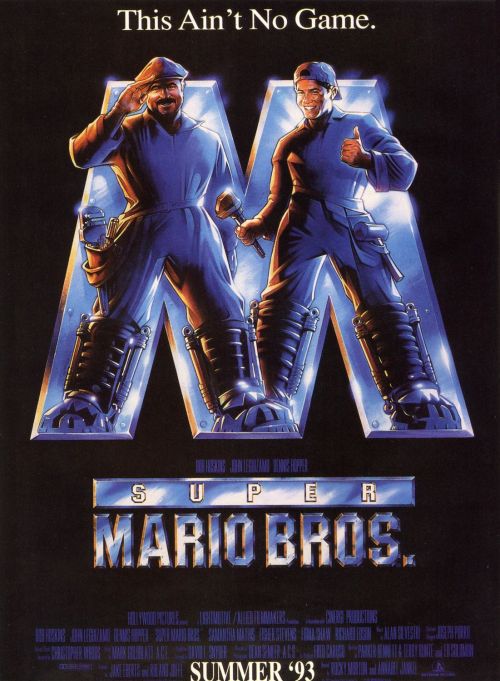

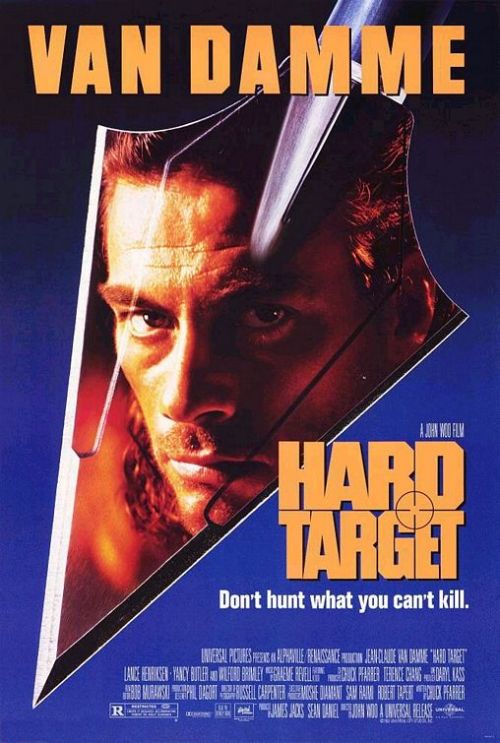

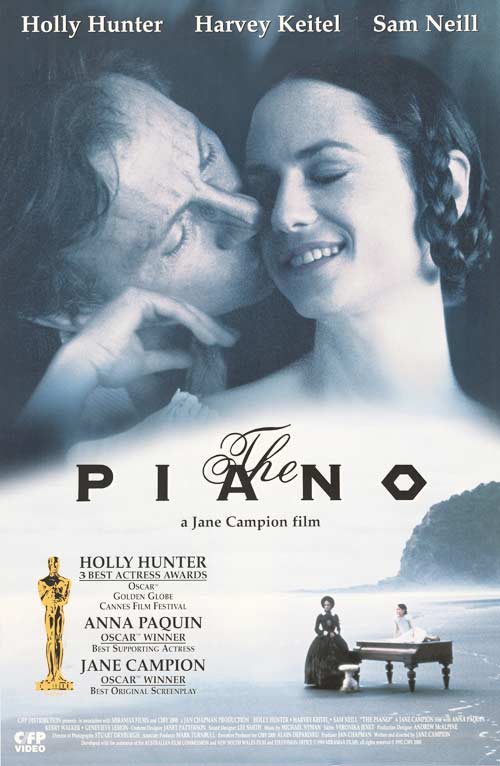

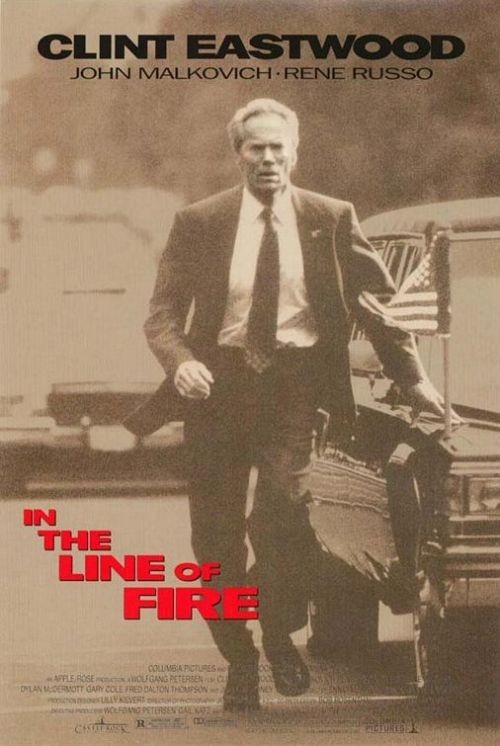

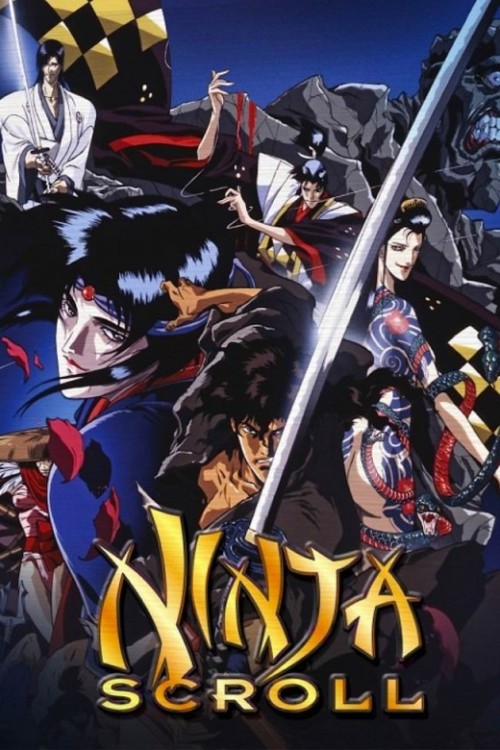

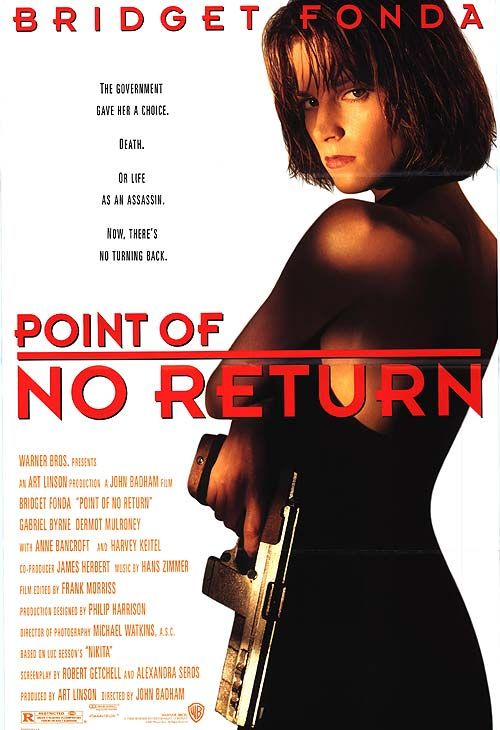

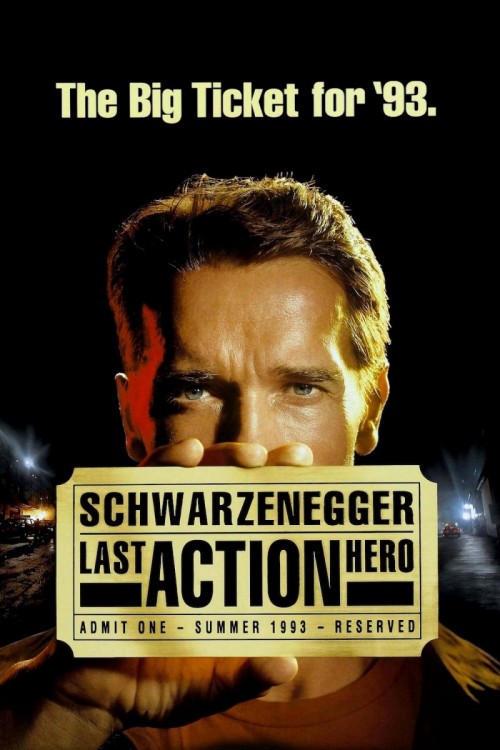

20/20 VISION ’93

20 striking movie posters from 1993.

I’ve seen a few of these lists already, and they all feature the same obvious choices (Jurassic Park is old LOL – we get it), so here are twenty less popular films from 20 years ago you might be surprised to learn are that old. Just think…one day, they’ll be as old as you. Gee, Wesley Snipes was popular, wasn’t he? Let’s kick it off, kohai.

20.

8.

June 3, 2012

THIS MUST BE THE PLACE

Far from being seen as the revolutionary step forward for videogames that was Sega’s Virtua Fighter (1993), Namco’s Tekken (1994) appeared as the flashier alternative to those who found VF‘s measured pace and extreme realism off-putting. Tekken was closer in spirit to the action found in Capcom’s Street Fighter II, and featured an entirely different control scheme to Virtua Fighter‘s – a four button setup, with one button assigned to each limb. The character models weren’t as blocky as Virtua Fighter‘s, and the characters were a much more eclectic mix than those found in Sega’s game. Iconic imagery – Paul’s skyscraper haircut, King’s jaguar wrestling mask, Yoshimitsu – flew in the face of VF‘s careful repackaging of familiar archetypes. Interestingly, the most radical addition to the VF cast, Siba, had been cut prior to the game’s release. An Arabian fighter swathed in robes and sporting a huge sword may seem like a classic stereotype, but compared to Akira, the gi-sporting, headbanded Ryu-knock who replaced him, Siba seems outrageous. Tekken took the archetypes, like the wandering martial artist looking for the true fight, and gave them a darker, more sinister spin; the wandering vagabond became a bitter, cowlicked revenger, the strongman became a mohawked robot, the primary female action hero became a villainous assassin. The fighting was full of special moves and unrealistic, over the top feats, in stark contrast to Virtua Fighter’s focus on realistic combat and real-life martial arts styles.

Perhaps the only area in which Tekken strove for realism was the background stages. As far back as the first Street Fighter (1987), visually impressive hand drawn backgrounds had become a staple of fighting games, and they were often based on real landmarks – SF1 features Mount Rushmore, for instance. But Street Fighter II had featured colourful backgrounds specifically tied to each fighter, each featuring theme music which subliminally served to strengthen the appeal and individuality of each of the characters. It worked – you’d encounter wild jungle beasts in Brazil and boxers in Vegas. Mortal Kombat (1992) featured a series of backdrops taken from its impressively realised backstory – the setting started off as a mysterious, Eastern-flavoured island, and as the game progressed, the fighting took place in front of increasingly menacing scenery. The game’s third stage features a visual teaser of the game’s penultimate boss character, and while the first stage sees you fighting in front of passive monks; by the end you’re battling for the tournament’s grandmaster, who patronisingly applauds the winner of the bout.

The essentially story-less Virtua Fighter featured none of this, instead showcasing a variety of pretty, yet generic areas in which to mix it up. It was clear that minimal attention had been paid to the backgrounds, and fair enough too – the fully realised 3D characters were what you were there to see, and making them fight was a close second. Tekken took a different path, setting each of its fights in a different location around the world, promoting the idea that it was a world fighting tournament, and that its competitors were from all over the globe. Unlike Street Fighter, the fighters weren’t tied to their specific countries (but this would change in Tekken 2 [1995]). Instead, the stages would cycle through randomly, but each featured their name at the bottom left of the screen, so as to add to the feeling that you were kicking a dude’s ass on a beach in Fiji instead of in the furthest reaches of a dank arcade on the wrong side of town. Also unlike Street Fighter, the backgrounds weren’t hand drawn; the designers used the considerable technology powering Tekken to create backgrounds that were considered at the time to be ‘photorealistic’.

Really?

Let’s today take a look at those backgrounds and see how they compare to their real life counterparts.

WINDERMERE

VENEZIA

SZECHWAN

MONUMENT VALLEY

CHIBA MARINE STADIUM

KYOTO

KING GEORGE ISLAND

FIJI

CHICAGO

ANGKOR WAT

ACROPOLIS

April 12, 2012

THE NUMBER 33

Have you ever wanted something you know you can never, ever have under any circumstances? This is a tale of pain and longing, magic and horror, loneliness and anguish. This is a tale of obsession, and how it can take you to the furthest reaches of the world. Lemme tell ya a story…

Back in the days of the corner shop, lollies were a big deal to a kid. Do you remember walking up to that shelf full of candy, armed with a $2 coin that could fill your pockets? Chocolate bars were obviously top tier, but spare a thought, dear reader, for those lesser confectioneries – Fizzy Cola, Fanty, those soft teeth, Milkos, Redskins, Toffee Apples…

Spare a thought, if you will, for those little individually wrapped pieces of bubble gum. You know, the ones packaged with temporary tattoos or stickers. You’d get a tattoo of a spider, or a sticker of a popular cartoon character, and all for 10c. Getting that little extra often made you felt like you weren’t getting ripped off. That extra novelty added so much. When it came down to choosing a piece of the gum or a mini Redskin, you’d suddenly picture that empty spot on your school folder that could do with a sticker of Pikachu.

Unlike you, the companies that mass produced the gum didn’t care what was on the stickers. Unlike you, they didn’t care what the flavour was, even though you know it’s that pseudo-strawberry you can still taste late some nights. The flavour didn’t even last a full minute most of the time, but it’s still indelible. It’s probably the fact that it’s so fleeting that makes it so memorable – the entire time it’s hitting your tastebuds full force, you’re memorising it so that in 30 seconds time, when the gum tastes like Blu-Tack, you’ll be thinking about that flavour and wanting another 10c piece, which also means another sticker.

At first, the stickers are a novelty and nothing more. As a kid, you might stick them all over your bedside table or chest of drawers, and because so many varieties are available on that lolly shelf, you end up with random scenes from a dozen cartoon shows. Freakier still are the stickers based on an entirely original IP. I once bought two pieces of gum and wound up with two ghastly images for my drawers: one was a cartoon picture of a kid being hit by a truck. He’s bleeding…he’s screaming. His skateboard lies on the road beside the pool of blood, and the faceless truck driver is about to run over that too. Above the carnage is the caption, ‘Horror!’ Yes, it is, but worse still is the next sticker: a cartoon picture of a jar full of eyeballs, severed limbs and…cherries. A label on the jar reads ‘Female Body with Cherries’. The caption above the scene reads ‘Ho Ho Horror!’, as if we’re laughing. As if ‘Female Body with Cherries’ is a joke, or witty at all. Even more disturbing is the idea that while the body parts in the fruit jar is meant to be the comedy variety of the sticker, that screaming kid being hit by the truck is just meant to scare you. It’s horror, and your red piece of chewing gum doesn’t seem so tasty now.

Eventually, if you buy enough of the gum at your corner shop on a whim, you end up with a fair amount of stickers. They’re often numbered, and you might get a streak: 5-8, 13-20. They might tell a story, or form a larger image. Something hooks you, and suddenly you wonder what’s stopping you from collecting the whole set. I mean, it’s not like you don’t buy the gum all the time anyway. Oh look, you just got number 22. It’s just that…you’d feel silly, wouldn’t you? Silly that you suddenly care about some cheap, stupid stickers that come with gum you buy because you’ve got 10c to burn and you don’t want two milk bottles. And yet…you wonder what number 21 looks like.

In 1994, Capcom’s popular Street Fighter characters made their bubble gum sticker debut in a set based around the then-new game Super Street Fighter II. It’s impossible to know how much success these achieved, but because Capcom is no stranger to sequels, 1995 saw another gum-sticker set released. Street Fighter Alpha: Warriors’ Dreams was a prequel game to Street Fighter II, depicting the characters in their younger days. The aging graphics of SFII were given a complete overhaul, with the characters of Street Fighter Alpha sporting an anime-flavoured look.

What better way to showcase this new look that with a series of gum stickers? The set was released in 1996, but somehow took two years to arrive at my corner shop. When they did, they were an instant hit. Finally, an IP we recognised! They were numbered. They were based on a game we played. They were 10c! The Street Fighter Alpha stickers filled the void that Oddbodz and Tazos had left, and unlike those trinkets, these could be stuck on schoolbooks and bedheads alike.

My wall was covered in them, particularly the ultra-common number 18. It felt like the rarity of each sticker came in waves. One month, number 20 would be all over your wall, and number 24 would be gold. The next, number 5 would be hated for being everywhere and number 29 would be hated for being nowhere. It was dynamic, and at 10c a pop, maddeningly addictive. Never did we stop to realise that something had gone fundamentally wrong – the stickers had overtaken the gum.

Not that we didn’t have fun with the gum; we were buying so many pieces trying to get those rare stickers, we’d end up with a tonne of the stuff. At one point, we had a contest to see how many pieces we could fit in our mouths. I’m man enough to admit that I won, with 23 pieces. When I finally spat it out, it looked like a tennis ball-sized brain.

The addiction worsened. We bought out the corner shop’s entire supply of Street Fighter gum, and the wait while the shopkeeper reordered was murder. When they finally arrived, we were furious – he’d ordered the wrong gum. The Street Fighter box was red, and in his ignorance he’d ordered another red box. Unfortunately, this red box was of gum with lame tattoos. Tattoos! We shouted at him for getting the wrong ones, and he informed us that he’d only get the Street Fighters back if we bought him out of the tattoos.

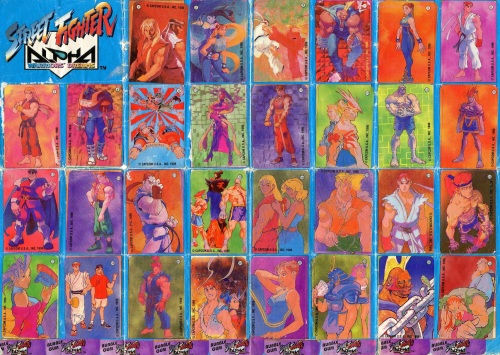

We looked like Kat Von D by the time the next box of Street Fighters showed up, and when it did, it came with a surprise. The shopkeeper didn’t just hand us our sacks of gum; he gave each of us a sticker album. This was a revelation – finally, we had a place to put our stickers. The album featured a series of monochrome placeholders for each sticker, which you’d then cover up once you got the corresponding sticker. At last we discovered just how many of the damn things comprised the whole set: 33.

All of a sudden, the race was on to complete your album. Double after double, piece after piece. Former commons became rare, former rares became wallpaper, but the true ultra-rares finally became apparent. By the end of the year, three of us had near complete albums. Only one sticker remained elusive – number 33.

It wasn’t like it was semi-rare, and only one asshole kid who wouldn’t trade it had one. It wasn’t like it was mega-rare, and you’d seen one once stuck to a bus stop, half torn off. It wasn’t even like it was SUPER-rare, and you’d gotten a misprint with the bottom half of number 32 and the top of 33.

There just wasn’t a 33.

We bought hundreds of stickers between us. We literally could have wallpapered an entire room with number 18. None of us ever, EVER got number 33. It was so damn rare that I’ve never even seen its image anywhere on the internet or elsewhere (UPDATE: RAE over at the amazing Street Fighter Miscellany has found the image. Not the sticker though. That ain’t happening.).

The monochrome facsimile on the back of the album stared out at us, mocking us. It waited and waited for us to finally open a 33, peel it from the backing and affix it, covering up the shame of an unfinished album. But the relief never came, and before long the shopkeeper had sold out once more, and informed us that the supplier had run out.

That’s right, we’d bought out the supplier, and still no number 33.

That was 1998, and this is 2012. This has tormented me for 14 years, and I suspect that in a cruel twist of fate, it will take another 19 until this is resolved.

The internet has proven useless. I have never, ever seen the album on any site, anywhere. The only evidence that they ever existed outside of the album I still own was a long-since-completed auction on eBay Germany for Street Fighter Alpha kaugummibilder, and another site selling a German equivalent of my album.

But it’s not my album.

There are two companies listed on the back of my album. Vidal Golosinas made the gum, and still makes confectionery today. Kuroczik Susswaren (sweets), on the other hand, appears to have made the stickers, and many other sets along with them, but it’s unclear whether or not they’re still in business.

Long ago, I accepted the fact that I’m almost completely alone in the world in owning (and caring about) this sticker album. This incomplete sticker album. The worst part is, it can never be complete. I’ve never even found the gum again, let alone the album.

I may own one of the rarest items in the world, and let me tell you, it’s a horrible feeling. So now I’m here, the last attempt at raising some kind of awareness of this. I could be completely wrong, and this Super Album could be completely common. Someone out there might have a room covered in number 33. I’ve never wanted to be wrong about something this much in my life. If you do know something…anything…let Wayning Interests know.

But somewhere, deep in the back of my mind, I know I’ve got this curse for life. Look upon it, ye Mighty, and despair.