Jack Nicholson, Burt Reynolds, and the role that shaped modern Hollywood.

I recently watched Terms of Endearment for the first time, and found it interesting to read that the supporting role of astronaut Garrett Breedlove, played in the film by Jack Nicholson, had originally been written for Burt Reynolds.

This made me wonder what kind of an impact such a small change would have made on the careers of both actors, and on Hollywood in general. While the supporting role of Breedlove, a character not found in the novel the film is based on, may seem insignificant in the scheme of things, the success of both the film and the role play a part in inspiring such supposition. Also important to consider are the careers of Nicholson and Reynolds, both considered to be at some point ‘the biggest movie star on the planet’, at the time the film went into pre-production in late 1982.

A TV and low budget film star since 1959, Reynolds’ big break came in 1972, when he appeared in Deliverance, a nightmarish thriller about four city slickers trying to survive a disastrous canoeing trip. His role as the most physical of the group established his image as a man of action, a reputation he cemented throughout the 70s in films like White Lightning, The Longest Yard and Gator. His greatest box-office success came with 1977’s Smokey and the Bandit, a Southern-fried action comedy which overshadowed his more interesting (but less well received) choices in the late 70s and early 80s.

Between 1977 and 1982, Reynolds had made two Smokey and the Bandit films as well as The Cannonball Run, a star-studded variation on the same theme. His 1982 musical The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas was the ninth highest grossing film in the US that year, but by that point, the public’s love affair with Reynolds was starting to cool. At the end of 1982 Reynolds found himself choosing between two scripts for his next film: Stroker Ace, an action-comedy about a NASCAR driver rebelling against the fried chicken chain that sponsors his team; or Terms of Endearment.

Nicholson, on the other hand, had become ‘the biggest movie star on the planet’ in 1975 after winning an Oscar for his performance in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, in which he played a criminal feigning insanity to avoid prison. The film’s director Milos Forman’s first choice for the role had been Reynolds, but the film’s producers felt Reynolds’ great fame might have caused the film to not be taken seriously. If you think about it, the loveable rogue role Reynolds played in his Smokey and the Bandit films is the fast food equivalent of Nicholson’s McMurphy in Cuckoo’s Nest.

Far less prolific than Reynolds, Nicholson only appeared in eight films between 1976 and 1982, including three in 1981 alone. His biggest success during this period was Stanley Kubrick’s horror film The Shining, an iconic and much needed hit for both Kubrick and Nicholson.

Despite receiving an Oscar nomination for his supporting role in Warren Beatty’s 1981 epic Reds, Nicholson felt burned out. After the critical and box office failure of The Postman Always Rings Twice later that year, Nicholson declared a temporary retirement.

Enter James L. Brooks. A TV producer responsible for The Mary Tyler Moore Show and Taxi, Brooks’ first foray into the world of films was 1979’s Starting Over, an adaptation of a Dan Wakefield novel which starred… Burt Reynolds. His next project, this time as writer, producer and director, was another adaptation of a novel – Terms of Endearment – about the lives of a widowed mother and her daughter over 30 years. For his adaptation, Brooks cast Shirley MacLaine and Debra Winger as the mother and daughter respectively, and added a love interest for the mother; a past-his-prime astronaut who helps her emerge from her shell.

Reynolds turned down the role of Breedlove, which Brooks had written specifically for him. It’s easy to see how Reynolds’ athletic physique, tough guy image, easy charm and deft hand at comedy would have suited the role, but for a variety of reported reasons it never happened. The most widely repeated story is that Reynolds was already obligated to do Stroker Ace. The more salacious stories say that Reynolds wasn’t willing to remove his hairpiece or appear out of shape for the role. Reynolds himself claims he was committed to Cannonball Run II, a story which doesn’t really hold water seeing as Shirley MacLaine also appears in that film. Whatever the reason, Reynolds passed, and Brooks set about looking for his astronaut.

James Garner was offered the role next, but clashed with Brooks over their differing interpretations of the character. Harrison Ford then turned it down, feeling uncomfortable with the age difference between himself and MacLaine. Finally, Nicholson was coaxed out of his self-imposed retirement, although Brooks had to talk him out of his by-then flat $3m fee; Nicholson settled for a percentage of the gross.

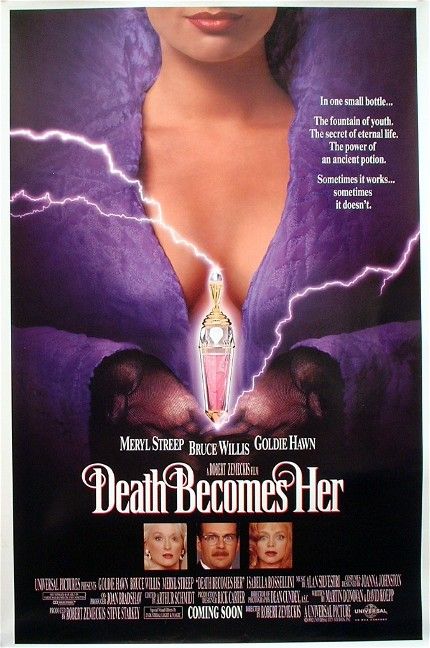

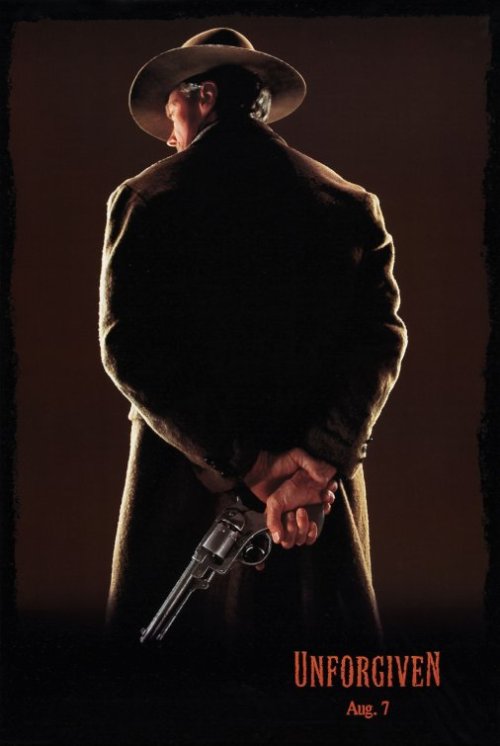

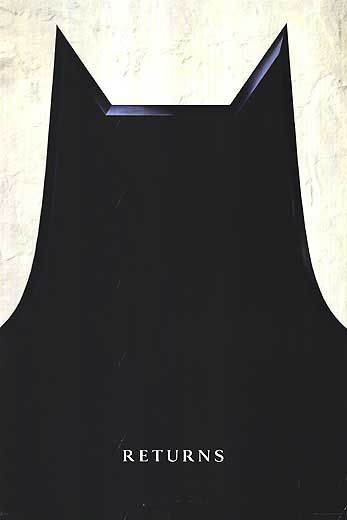

Terms of Endearment was released in late 1983. It grossed over $108m in the United States alone, and won five Oscars from a total of 11 nominations. Among the Oscar winners was Nicholson, who received the Best Supporting Actor award. The success of the film imbued him with renewed box office clout (as well as a $9m payday), allowing him to once again pick and choose his projects. This began a streak of critical and financial successes throughout the 80s, culminating in the role that earned Nicholson what is still the biggest paycheque ever for an actor; the Joker in Batman. Creatively, however, Nicholson followed the Brando method; the more bankable he became, the less effort he put into his performances. While smaller movies like Ironweed and Prizzi’s Honor benefit from true performances, bigger budget films like The Witches of Eastwick and The Shining tend to riff on Nicholson’s public persona. Batman arguably epitomises this trend.

Stroker Ace was also released in 1983, beating Terms of Endearment to the box office by a few months and grossing $13m in the United States. It was nominated for five Golden Raspberry Awards, and in a perverse parallel, won one for Jim Nabors as Worst Supporting Actor. The film’s failure effectively ended Reynolds’ association with the hillbilly fast car genre, relegating him to forgettable ‘hard boiled cop’ films for the rest of the 1980s. While Nicholson was joy-buzzing gangsters in Batman, Reynolds was a dog avenging his own death as a ghost in All Dogs Go to Heaven.

Even if Cannonball Run II was the movie Reynolds took over Terms, it only grossed $28m upon its United States release in 1984. It was nominated for eight Golden Raspberries, and either counter to or in affirmation of its ineptitude, won none. Reynolds himself has since said that turning down the role was the ‘stupidest thing’ he ever did, and that taking the role ‘would have been a way to get all the things’ he wanted. While that’s not especially heartening given that all he seemed to want to do at the time was racing movies, it’s easy to imagine that the big paydays they offered were keeping him in check, forcing him to scrimp and save until he could finally do whatever it was he really wanted to. Of course, there was that whole bankruptcy thing, so maybe not.

Now let’s say that Reynolds had taken the Breedlove role in Terms of Endearment. Assuming the movie was as successful with Reynolds in the role (there’s nothing to suggest Nicholson was the major drawcard to the film at that point in his career – even the marketing downplayed his involvement), this would have been the film to propel him out of Smokey and the Bandit‘s shadow and prove that he was capable of more. Furthermore, coming as it did in 1983, it would have capped his previous run of financial successes and set him up as a bankable and versatile comedic and dramatic actor heading into the 1980s.

Taking a risk like Terms at a time when Hal Needham seemed to drive the proverbial dumptruck full of money to Reynolds’ house every six months might have given him the confidence to take some other riskier roles offered to him later in his career: John McClane in Die Hard, Richard Gere (you know you don’t know the character’s name either) in Pretty Woman, perhaps even Daryl Van Horne in The Witches of Eastwick. It’s also conceivable that had Reynolds been the most bankable star in the world by 1988, he may have been offered the role of Batman, as was rumoured at the time.

If Reynolds had played Batman, it’s likely Tim Burton would not have directed it; with Reynolds on board as the title character, he would have had the clout to pick and choose his crew, and the emphasis of the hero over the villain would have dissuaded Burton’s involvement anyway. This would have made the film conform to the superhero movie archetype established by Superman in 1978, or, at worst, resulted in Jokey and the Batman. Either way, the precedent that Burton, Nicholson and Michael Keaton worked to establish with their offbeat take on the comic book film wouldn’t have existed in 2000, when Bryan Singer kicked off the current era of superhero movies. Nor would Batman‘s enormous success have been achieved, and all the permanent changes to the Hollywood system that came with that. Without Batman, we might now live in a world without Superman Returns, Hulk, Spider-Man 3, Jonah Hex, Ghost Rider, Daredevil, Catwoman…hmm.

The failure or even mediocrity of the much-hyped Batman would have been a part of Reynolds’ overexposure by the early 1990s, leading to a career lull which Boogie Nights would still have been able to pick up…

That said, had Nicholson not had the success of Terms of Endearment, it’s likely he would have stayed semi-retired until the opportunity arose to make his pet project; Chinatown sequel The Two Jakes. Nicholson was trying to make Jakes as early as 1984, but production problems kept the film in development hell until 1990, when Nicholson himself stepped up to direct it. Had he not made Terms, and his efforts were poured into the comfort zone of Jakes instead, it’s likely this would have capped his string of critical and financial failures of the first half of the decade, and encouraged him to prolong his retirement. Not working with Brooks on Terms of Endearment means he would not have taken his uncredited, unpaid role in Brooks’ followup Broadcast News. Nicholson has said that at the time of Terms, he was involved in a film version of The Mosquito Coast, playing a role that eventually went to Harrison Ford. This may have gone ahead without the success of Terms. Witches of Eastwick director George Miller’s first choice for the role of Daryl Van Horne had been Bill Murray, and had Nicholson not been as bankable or busy on The Mosquito Coast, producers Jon Peters and Peter Guber would not have chosen him over Murray. This of course means that Peters and Guber would have had no prior relationship with Nicholson when approaching him for their next big budget film – Batman.

Nicholson’s portrayal of the Joker galvanised in the public eye his image as an actor in the later stage of his life. It’s arguable that since Batman, Nicholson has played variations on his own public image in film after film, with few exceptions. Reynolds is another actor who was often accused of playing himself. It’s interesting that 1997 brought the both of them roles which would appear as extreme riffs on their respective public images – Melvin Udall in As Good as It Gets for Nicholson and Jack Horner in Boogie Nights for Reynolds – but would also earn each of them Oscar nominations. Nicholson won his third Oscar for his role, but Reynolds lost out to Robin Williams for his role in Good Will Hunting. At a time when winning an Oscar was all about promoting comebacks, Reynolds’ loss was surprising, and led to the last 15 years which he has spent riffing on his public image, culminating in his role as himself in the videogame Saints Row the Third.

Nicholson’s 1997 Oscar win – for a James L. Brooks film – assured his legendary status, and has afforded him the luxury of appearing in only seven films in the last 15 years. Of these, arguably only About Schmidt has tested his acting skills. It’s likely that without the success of Terms of Endearment, Nicholson would likely have returned to being an actor, rather than a movie star, and could have ended up in the Jack Horner role in Boogie Nights.

The paunchy astronaut with a taste for younger women might have been a minor player in the film of a book he wasn’t even in, but clearly the case of Garrett Breedlove highlights the importance of casting and the relevance of Stanislavski’s saying: “There are no small parts, only small actors.” In this instance, the actors were both so huge that it was more of a ‘this town ain’t big enough for the both of us’ situation.

Then again, perhaps I’m overthinking it.

![Bicentennial_Park_12[1]](https://wayninginterests.files.wordpress.com/2012/04/bicentennial_park_121.jpg?w=500&h=375)