Synopsis: Nineteen-year-old Tony Manero lives for Saturday nights at the local disco, where he’s king of the dance floor. But outside of the club, things don’t look so rosy, and Tony becomes disillusioned with the life he’s leading.

The nearest we’ve come [prior to John Lennon’s murder] to rock and roll news that inspired the mass imagination, that momentarily melded a disparate, casual-to-fanatic audience into something like a community, was (don’t hold your breath) Saturday Night Fever. – Robert Christgau

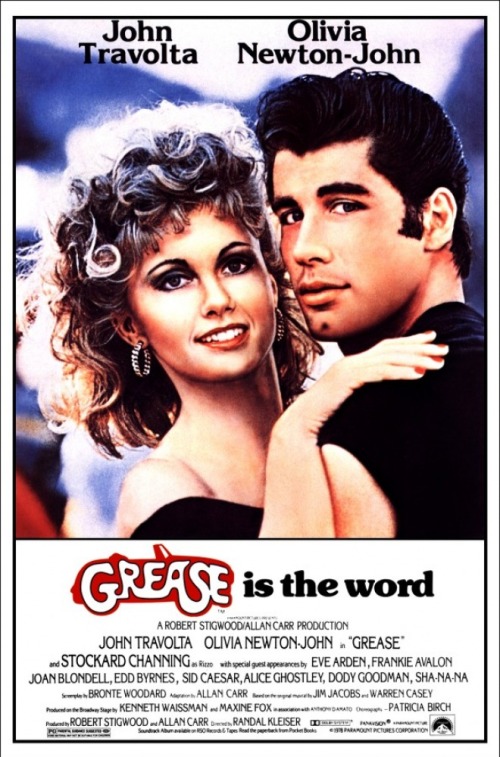

A remarkable thing about John Badham’s iconic Saturday Night Fever is that it seems to have been made with an incredibly forward-thinking mindset. Whereas Grease (1978) coasts by on an artificial charm afforded it by the 50s-60s nostalgia that was all the rage in 1970s pop culture, Fever captures the spirit of its era with an arresting immediacy. Grease feels like both an attempt to showcase 50s kitsch that had up to that point avoided pop culture’s scrutiny, as well as a shameless cash-in on that wave of nostalgia, and as such it’s a film that feels like a 70s take on the 50s. Saturday Night Fever, with its prescient use of 70s iconography, feels like it could be made today, should someone feel like making a 70s youth-angst piece.

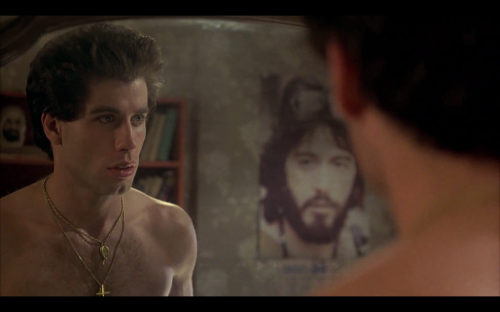

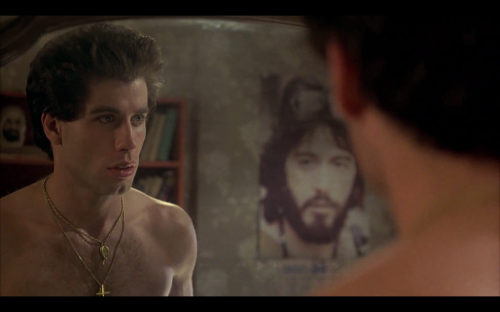

Take the scene where, to the crystallised melancholia of the Bee Gees’ “Night Fever”, Travolta’s Tony prepares his glossy mane for a night at the 2001 Odyssey (itself a fantastically affected reference) disco. Intercut between shots of an underwear-clad Tony and his dimly lit, imperfectly synchronised disco fantasy are shots of posters he has up around his bedroom: Bruce Lee. Farrah Fawcett. Rocky. Lynda Carter as Wonder Woman. Serpico.

As you read those names, the images that spring to mind are most likely the very same as shown in the film. In fact, if I were to describe to you a scene in a movie where John Travolta dances to disco music with posters of Bruce Lee and Farrah Fawcett all around him, you’d be forgiven for thinking I was describing some kind of 70s nostalgia sketch comedy skit; it’s just that iconic.

Expanding upon this concept is a later scene where Tony reflects on the previous night’s disco adventure, during which he’s mistaken for Al Pacino. Unable to wipe the shit-eating grin (SEG) of flattery off his face, he proceeds to stomp around the house shouting “Attica! Attica!” ala Pacino in Dog Day Afternoon (1975).

Imagine a movie from this decade (2010s) being so immediately iconic that a key scene is referenced in another film just two years later, and not in one of those Disaster Movie parodies. And once you’ve done that, imagine the kind of filmmakers who could not only recognise that iconography, but channel it into their story seamlessly, without evoking any wanker hand gestures from the audience. And on top of THAT, imagine that the film that channels all this 70s pop culture iconography eventually becomes one that essentially defines the decade.

It’s just that iconic.

In fact, almost everything you need to know about John Travolta’s Tony Manero is provided by the – there’s that word again – iconic opening scene in which he struts down a Brooklyn street to “Staying Alive”. As quickly as the film presents the image of a confident, cool, modern young man, it undermines it by adding a dark undercurrent of misogyny as he stops mid-strut to harass a young woman going about her day. He doesn’t get her number, but we’ve got his. And then, without missing a beat, he continues on his way, a journey that will lead him out of ‘da neighbourhood’ and into a wider world, one he only thought he knew. It’s incredible storytelling by all involved, we understand completely this man’s wants and needs, even if he doesn’t. You can imagine the audiences of the time torn between feeling repelled by Tony and wanting to be him (or be with him).

Travolta’s performance seems to come from a completely different place from either Vinnie Barbarino, still nasally inserting rubber hoses on the small screen at the time of the film’s release, or the trio of oafs he’d portrayed on the big screen thus far. It never once feels affected, and you get the sense that although he may not have lived Tony’s life, he’s channeling someone who has. Tony is completely without the mannerisms that tend to overwhelm Travolta’s characters since, and even when confronted by the film’s colourful supporting cast, he always feels intact.

More importantly, he’s sympathetic, even if we’re constantly faced with his character flaws and poor treatment of women (much of which seems to be informed by his father, around whom the Manero family seems to revolve). I’d argue that this sympathy is entirely Travolta’s contribution, as it’s easy to imagine Tony as a completely unlikeable brute in the hands of a more severe actor like Pacino or Robert De Niro. Travolta’s natural charm and charisma go a long way in making believable a young man who is “king of the disco”, and even that such a position could exist. That by the end of the film, even after his totally indefensible behaviour, we feel his sadness and get a sense of hope that he might be able to change speaks a lot to the depth of Travolta’s performance. We don’t just see the lad of the surface, but we glimpse the man he could become. Funnily enough though, it’s never at all what’s depicted in the sequel…

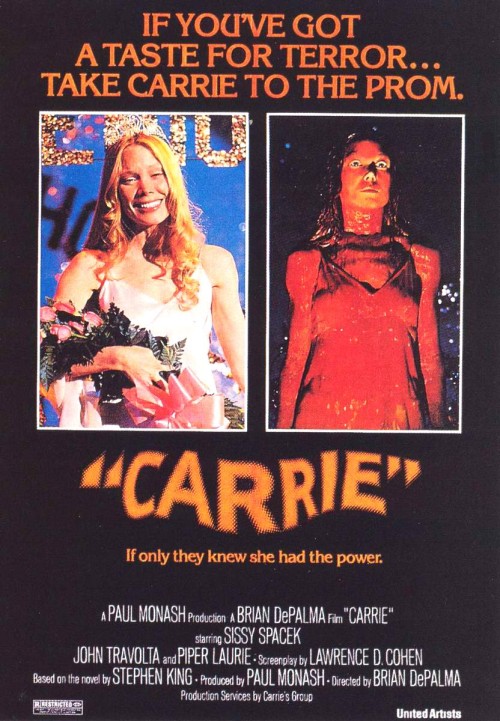

Whether or not Tony is a character deserving of such a performance is another matter entirely. To its credit, this film highlighted a particularly disenfranchised section of society at the time – young, second or third generation immigrants, specifically Italians, overlooked by the grand operatics of The Godfather or the comic-book miracles of Rocky. Fever instead depicts those who went to see those films (Tony’s Rocky poster and Dog Day Afternoon impression), the kind of people who model themselves on what’s hot and popular. Tony Manero is defined by his disco prowess – that’s just who he is, and it seems like that’s all that he’s happy to be. As the viewer, it’s hard to understand how this would be enough for anyone. When he’s not at the disco, he’s a non-entity, albeit a charming one, at his worthless job, and he’s a burden and a failure at home. But as soon as he hits that lit-up multicoloured floor, he’s the man.

For a movie that so defines the era in the public consciousness, it’s amazing just how contemptuous of disco Fever is. The movie’s tagline, ‘Where do you go when the record is over…’, positioned on the poster just above the indelible image of the white polyester-clad Tony with one arm in the air, unsubtly suggests that the film’s very purpose is to question Tony’s existence, and in doing so, that of anyone who identifies with him and his passion. It’s tough to imagine a movie in modern times being so unafraid to openly question not only its protagonist, but any viewer attracted by the platform shoes and stylised logo. It’d be like if the tagline of the latest CGI blockbuster read ‘Are you really this stupid?’

Travolta’s dance moves in the film are impressive, and the disco scenes are filmed with an electric intimacy that makes them a glossy highlight. There’s no effort being made to glamourise the place though: the movie just captures the disco, in all its drab, tacky, fire hazard glory, as it existed, and thanks to the great work of the filmmakers, as it will always exist.

I’m always fascinated by an early disco scene in which the crowd seems to fall into line all at once. As “Night Fever” once again permeates the disco like a smoke machine, the dancers, most looking almost bored in their procedural technique, begin to dance as one. The movements aren’t in perfect sync either, a neat little detail which gives it an added sense of realism. Some, like Tony, are better at it, some aren’t. You don’t feel that there’s some Hollywood choreographer off-screen yelling at people to get it right, it’s just what people did back then. It’s not even like they’re following anyone’s lead – they just fall into place. That’s the kind of dancing they were doing in the discos, it’s a routine, and they just do what they know as the cameras roll.

It’s in the disco that Tony meets Stephanie, a Brooklyn gal who’s trying to make it across the bridge in the big city, and who represents the kind of progress Tony would like to make for himself. Tony and his buddies are dazzled by her dance moves (although I have no idea why), and he wastes no time trying to get to know her. He can see that they come from the same place, and he calls her out on her pretensions just as she calls him out on his lack of sophistication. She’s a little older and a little wiser, but that doesn’t stop Tony from trying to turn her into an object. You get the sense that that’s the easiest way for Tony’s kind to be able to deal with women; if they’re not actual people, they’re much simpler conquests and there’s none of that messy emotional stuff to deal with. But he sees Stephanie as a way out of his rut, whether she wants to be or not.

On the other end of the scale is Annette, a pathetic groupie from the disco. Whenever Tony’s on the scene, she’s there, trying her best to convince him to be with her. The desperation disgusts Tony, and he’s not the slightest bit interested… but his friends are. Tony complains that on their one date together, all Annette could talk about was her married sisters, and this adds a tragic degree to Annette’s struggle. So desperate is she to get what she wants, she’s willing to lower her own sights from marriage to purely sex in a hopeless attempt to get Tony’s attention. On the other hand, Tony’s callous refusal to have anything to do with her stems from her representing the ultimate commitment, one that would seriously cramp his style at the 2001. At one point, Tony directly asks Annette if she’s “a nice girl, or a cunt?” Immediately, Tony’s view of women is galvanised, and it’s easy for the viewer to guess which category the film’s other women fall into in Tony’s eyes. To Annette’s credit, her (perhaps unwittingly) challenging reply: “I dunno. Both?” Tony’s quick to dismiss the possibility.

The way he reacts to these two very different women is a fantastically canny observation and interpretation on the part of Travolta and the filmmakers of how young men like this operate. As often as he rejects Annette, Tony doesn’t see the parallels in how often he’s rejected by Stephanie, and never tries to understand that the same reason the rejection makes him even more persistent is the same as it is for Annette. Tony aches to turn, to downgrade, a symbol of progress and sophistication into a fuck, while a girl who presents herself as nothing but a fuck holds zero appeal for him because there’s nothing for him to work with. Yes, it’s disgusting, but it’s also honest.

Eventually, jealousy turns out to be his weakness in both cases – Annette is able to temporarily tempt him into sex by threatening to have sex with his friends instead, while Tony becomes enraged upon learning of Stephanie’s FWB. The jealousy immediately serves to turn both women into objects he feels he’s entitled to control, and both scenes have some truly horrid ramifications down the track for all involved.

One misstep in the film is the subplot about Tony’s brother, a priest who is having doubts about his faith. There’s a very subtle indication that the reason for his troubles may be because he’s gay, but the whole thing is dealt with in such an uncharacteristically wishy-washy manner that it makes you wonder why they bothered, especially when the film’s vitriol is purely directed at Tony and his ilk. On top of that, the actor playing Tony’s brother looks nothing like Travolta, and significantly older than him to boot. Just…why?

Speaking of ilk, the most repellent characters in the film are Tony’s friends, three creepy, completely one-dimensional louts who accompany Tony to the disco as part of their weekly ritual. They swear, they laugh, they drink, they fight and they fuck (consensual or not). Like Tony they’re racist, but unlike Tony, there’s no redemption or self-improvement on the horizon. Many of Travolta’s best and most subtle moments are his wearisome reactions to his friends’ antics. It’s clear from the first scene in which they appear that Tony knows they’re a dead weight, but ‘guyz gotta stick togetha’, and as a pack, they’re integral to his effectiveness at the disco. It could be that Tony’s complete effectiveness as one of the great three-dimensional characters in cinema is in part due to the one-note characters who surround him, but it’s really all down to Travolta’s performance.

The soundtrack, so epic in its success, deserves a mention here. What I find interesting about the film’s use of the Bee Gees’ songs is how they alternate between being played as actual songs in the disco, as is “Night Fever”, to existing purely as an inner rhythm just for Tony, as is “Staying Alive” and “How Deep Is Your Love”. It’s an effect powerful in intent and seamless in execution.

In its sole appearance in the film, “Staying Alive”, with its relentless beat, truly serves as Tony’s rhythm of life. The bleak lyrics seem to say as much about him as his cocky strut, and its fade-out coincides with Tony’s first appearance in his work uniform. As soon as he leaves work, it’s back at full volume, but once he gets home and is forced to conform to the rules of the household (read: his father), it fades out for good.

A rare non-Gibb related song plays when Tony first enters the disco – Walter Murphy’s “A Fifth of Beethoven”. The track’s inclusion at this introductory scene for the disco itself seems to suggest disco’s place within the culture: even Beethoven has had to bend over for this unstoppable juggernaut of a trend.

It’s followed up by “Disco Inferno” by the Trammps, suitably played as Tony and Annette exchange some sick burns before Tony turns his attention to burning up the dance floor, quickly stealing all the attention from poor Annette, who’s trying way too hard as usual.

Everyone at the 2001 Odyssey’s impressed by Tony’s dancing, but the only dancing he wants to see is a stripper in the bar section. It’s a particularly well-staged scene, with Tony placed between the stripper and Annette, desperate to talk Tony into taking her to the backseat of his car. As Tony rebuffs Annette’s advances with barely a word, she’s forced to stare at his preferred object of lust, all while Yvonne Elliman’s wistful “If I Can’t Have You” plays in the background. It’s fucking cruel, and it’s to the credit of Travolta and particularly actor Donna Pescow (Annette) for making it so powerful. The scene ends with Annette seemingly content with the fact that she’s more top heavy than the stripper, and her self-satisfied smile reveals she’s paid no heed to Tony’s misgivings.

Rick Dees’ satirical novelty hit “Disco Duck” appears briefly in the dance club, further solidifying the underlying contempt the film has for disco. The music sets the pace as a sleazy dance instructor offers some particularly misogynistic observations of Stephanie to Tony, all while trying to teach some seriously unhip folks to dance disco-style. The message is pretty clear.

When the final song of the film, “How Deep Is Your Love”, appears, it seems to be a direct challenge to Tony’s character. While the song itself is a pretty sappy piece of work, its meaning in this context – Tony is endlessly travelling back and forth on the subway, forced to reassess his entire life after nearly raping Stephanie and witnessing the (overly melodramatic) suicide of one of his odious friends – seems to be asking if Tony has what it takes to rise above a life that’s gone past the point of no return. The ending, in which he enters into a friendship of equality with Stephanie, perhaps the first adult relationship he’s had in his life, seems to suggest that he has, while the film’s dire sequel suggests that he hasn’t. In terms of his performance, it’s also Travolta’s best scene in the movie.

By the film’s end, it’s unclear as to whether or not the Bee Gees and their music exist in Tony’s world the way they do in ours. It’s not like he has any posters of them up in his room, and the majority – if not all – of songs performed by them are used like Tony’s internal monologues. While the other songs played at the disco are mixed into the soundtrack as if they were being played, the Bee Gees tunes all have a strange, dubbed-in ethereal quality to them, as if Tony and the audience are the only ones who can hear them. When Tony and Stephanie are practicing at the dance hall, the record he plays is a cover of the Bee Gees’ “More Than A Woman”. Why not use the original? Perhaps the reason for failure of subsequent attempts at this kind of film, including the lamentable Staying Alive, was due to a lack, or a poor understand of, this very technique.

It’s interesting that in these modern remake-heavy times, no one’s dared an attempt to remake Saturday Night Fever. When you strip away the tacky disco veneer, the story – a young man grows up – is timeless, and coupled with whatever music is currently popular, you’d think it’d be a no-brainer. In the decades that followed the original, where was Patrick Swayze in a new wave Fever? Will Smith in a hip-hop Fever? The dude out of Star Wars Episode III in a nu-metal Fever? Channing Tatum in a dubstep Fever?

With over $120m at the box office by the end of its eight month (!) run in theatres, and coming off a budget of $3m, Saturday Night Fever, the film, was a major success. The soundtrack, by comparison, was a phenomenon, remaining in the charts for over two years. John Travolta received an Oscar nomination for what was his first real starring role, and I believe much of the film’s success is down to him. He was so popular at the time thanks to Welcome Back, Kotter that Fever had a built-in audience from the green light, it just happened that that audience – teenage girls – weren’t able to see the R-rated movie.

The filmmakers were caught in a particularly volatile time in entertainment history – with the release of Star Wars in the same year, the path to financial success suddenly seemed crystal clear: get the young people in. The R-rated Fever was a movie created with that very 70s, story-driven, realistic mindset pioneered by Midnight Cowboy and The Godfather, and perhaps this was overreaching for a film that could have – and did – become a blockbuster as a kid-friendly film. At the same time, had it been packaged as a cutesy Grease-style disco flick in the first place, it likely wouldn’t have inspired such a powerful performance from Travolta, nor would it have earned the critical accolades that helped more than just horny teens buy $120m worth of tickets. But, those Hollywood fat cats noted, those horny teens had cash, so…

A 1978 re-edit omitting the rape scenes and foul language (and with them, a lot of the film’s pathos) was hastily rushed to cinemas in the hope of cashing in on the Grease phenomenon, and the money just kept rolling in. To the Hollywood execs, this was as clear a sign as any that films don’t particularly need substance to succeed, the effects of which we’re feeling all too often today.

Just what was it about the role of Tony Manero that turned John Travolta into a legitimate superstar? Perhaps it was that the film gave disco – previously confined to an underground following mainly made up of blacks and gays – a white, hetero, male face. Suddenly, it was okay to be into it because that cool Barbarino guy was into it. And even if you were too young to see the movie, the image of Travolta in his suit was everywhere, and wherever it wasn’t, the music was. You didn’t really need to have seen the film to get the gist: Travolta played a disco superstar, and his soundtrack was everywhere. As I mentioned, the film’s clever use of the Bee Gees songs as Tony’s internal rhythm meant that when you heard the songs, you’d be able to channel your inner Tony and become a disco king (or queen) yourself.

Or perhaps it was that through his remarkable performance, Travolta completely loses himself in the role. He gifts Tony with his natural charisma, and lets the character do the rest. Unlike almost every other Travolta film (and certainly many recent ones), you never once feel like you’re watching John Travolta, you’re watching Tony Manero’s life play out. It’ll be interesting to see if he’s once again able to achieve such a transformation during this series.

Saturday Night Fever was pretty much confined to the relic pile in the years after its release. It’s that 70s movie, the disco one, that John Travolta Bee Gees shit. In many ways, Fever was a victim of its own success, and when it went down, it made sure to take a lot more with it. It’s a lesson Hollywood and the entertainment industry seem to have actually bothered taking on board, and with good reason.

In the wake of Fever‘s unprecedented and apparently wholly unexpected success, so many copycats – Thank God It’s Friday, the shameless Disco Fever, Disco Godfather, Roller Boogie – sprang up in its wake and eroded its power. Grease, often coupled with Fever, was arguably trying to bank on Fever‘s success – two Travolta musicals in as many years ain’t a coincidence – but at least it had the courage to wear a different coat of paint. As such, Grease’s reputation remained essentially intact during the years that Fever, and Travolta, became relics “of an era we were trying to forget.” The clones all make the same mistake – openly wallowing in campiness, which Fever never once indulges in. We can laugh now at the tackiness of the fashion and sense of style, but back then, this was it.

In fact, Saturday Night Fever‘s immense popularity and the tireless work of its at-the-time ubiquitous soundtrack to drag disco into the mainstream caused the death of the genre. By 1979, overexposure had led to backlash, culminating in Chicago’s infamous Disco Demolition Night in July of that year. The Bee Gees, arguably the most popular pop act of the late 1970s, were all but finished by 1980. So too was John Travolta, but that’s a story for another time.

It’s not enough to say that Fever was a victim of its own success. In becoming the match that started the Disco Sucks fire, yet still being an undisputed megahit, Saturday Night Fever‘s patricidal antics put it in a very unique place in pop culture history, up there with E.T. for Atari, Be Here Now, and Guitar Hero.